Annual Meeting 2025 Preliminary Schedule Now Posted

Check out the condensed program and schedule at-a-glance for the fall’s BMES Annual Meeting in San Diego, Calif., now posted here: ...

BMES serves as the lead society and professional home for biomedical engineers and bioengineers. BMES membership has grown to over 6,700 members, with more than 110+ BMES Student Chapters, three Special Interest Groups (SIGs), and four professional journals.

Welcome to the BMES Hub, a cutting-edge collaborative platform created to connect members, foster innovation, and facilitate conversations within the biomedical engineering community.

Discover all of the ways that you can boost your presence and ROI at the 2024 BMES Annual Meeting. Browse a range of on-site and digital promotional opportunities designed to suit any goal or budget that will provide maximum impact.

This is one in a series of articles highlighting some of the technologies, processes and keynote plenary sessions presented at the 2024 Annual Meeting of the Biomedical Engineering Society, October 2024.

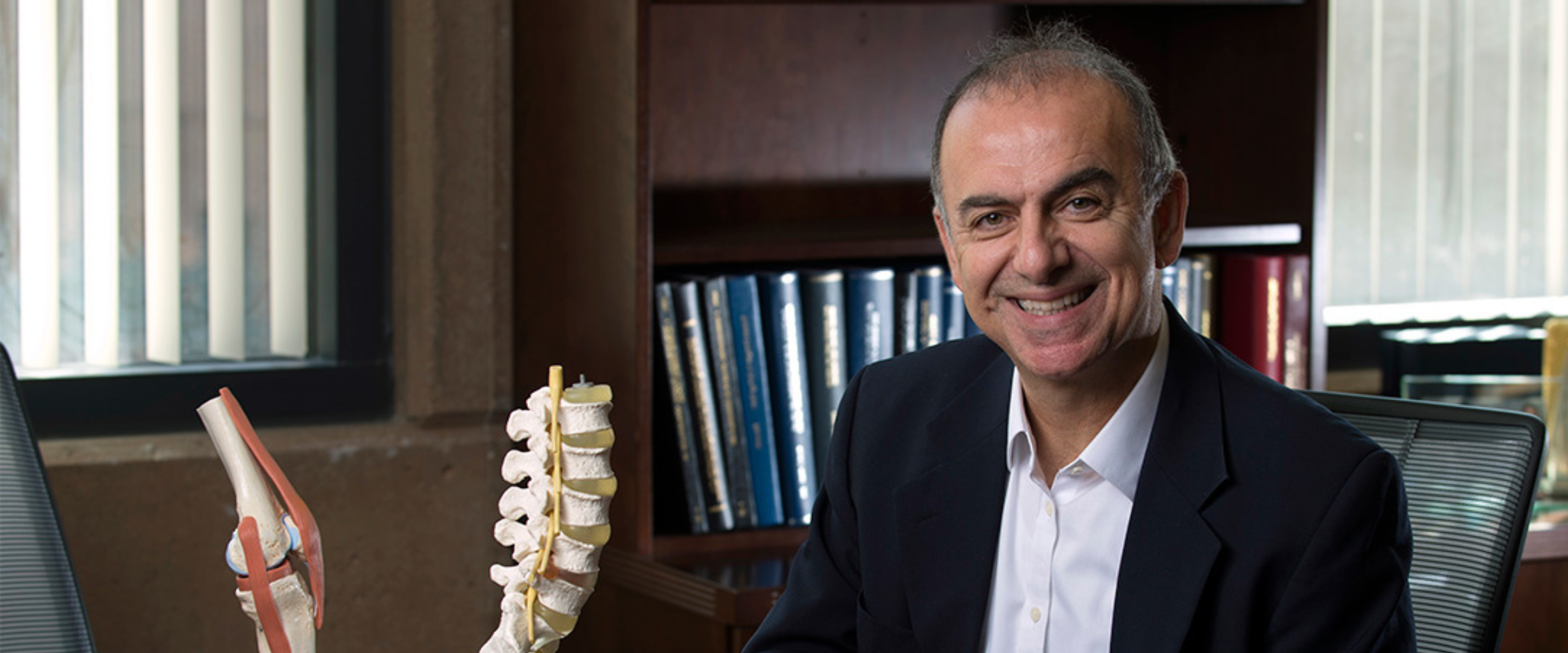

When Kyriacos A. Athanasiou, the winner of the prestigious Robert A. Pritzker Distinguished Lectureship Award, addressed BMES members at the recent BMES 2024 annual meeting, he did more than recap his research.  He also gave some surprising advice on how to succeed in research and also in life.

He also gave some surprising advice on how to succeed in research and also in life.

Athanasiou’s observations draw their roots from an illustrious career. A Distinguished Professor at University of California, Irvine, and BMES Fellow, he served as BMES president from 2003 - 2004. He holds 34 patents and 15 FDA-approved products, and he and his students launched multiple companies, one of which is pioneering scaffold-free cartilage tissue generation.

Building on Bone

After receiving a PhD in mechanical engineering from Columbia University in 1989, Athanasiou joined the University of Texas Health Science Center. There, he pioneered the use of bioresorbable scaffolds seeded with growth factors as bone and dental fillers. His team extended the technology to heal focal lesions, small areas of damaged tissue, which interfered with smooth and frictionless bone-to-bone movement.

While in Texas, Athanasiou founded OsteoBiologics to commercialize the technology. Smith & Nephew acquired the business for $72 million in 2014.

He also discovered, quite by chance he says, that some trauma patients who undergo shock cannot receive intravenous medicines. Given his understanding of bone tissue, he thought it might be possible to deliver drugs and blood by routing them through bone instead.

He formed VidaCare to translate those insights into an actual product. Named EZ-IO, the intraosseous infusion system was approved by the FDA in 2004 and quickly established itself as an emergency medicine go-to around the world. It was even featured in a number of television shows, including “ER,” “The Resident,” Gray’s Anatomy, and National Geographic’s “Inside Combat Rescue.”

In 2013, Teleflex Medical acquired VidaCare for $263 million.

Growing Cartilage Without Scaffolds

Athanasiou joined Rice University as a full professor of engineering for 10 years, before joining the University of California, Davis, in 2009 as chair of biomedical engineering. In 2017, he moved to the University of California, Irvine. New schools meant new research directions and a new spinoff, Cartilage Inc., led by Athanasiou’s wife, Kiley Athanasiou. Its research agenda is ambitious: engineer biomimetic cartilage that looks and acts like the real thing without using any exogenous scaffolds of any sort.

“We’ve been working on this process for 24 years,” Athanasiou said. “We want to engineer a tissue that is biomimetic, not only in terms of appearance, but also in terms of biomechanical and biochemical characteristics. We call this the self-assembling process, and it doesn’t use scaffolds of any sort.”

Osteoarthritis and other types of cartilage damage in joints throughout the body affect tens of millions of people in the United States alone. Unfortunately, cartilage cells do not regenerate, and current therapies cannot heal cartilage damage. Common treatments include total joint replacements.

Athanasiou attacked the problem by fully characterizing the type of biomechanical forces and other exogenous signals that activate single cells as they grow. Then he duplicated them on engineered tissues.

“We squeeze them, we indent them, we shear them, and we look at their behaviors and gene expression,” he explained. “Then we go to the tissue level, and we try to drive tissue engineering with hydrostatic pressure, direct compression, and other mechanical forces. For example, we show that we can use shear to increase tensile and compressive characteristics quite significantly.”

Along the way, his team designed tensile bioreactors that put tissue under stress by stretching, yielding cartilage properties on par with native tissue.

Even more importantly, he found a way to generate large numbers of cartilage cells. Ordinarily, culturing and growing cartilage cells causes them to differentiate and lose their ability to make tissue very rapidly.

“So, we developed new approaches that allow us to take human chondrocytes and expand them 12 million times without losing their ability to form tissue,” he said. “We can take a biopsy the size of a sugar cube and get enough cells to potentially cover the jaws or knees of over 35 million patients.”

Cartilage Inc. has developed several products based on this technology. It includes implants that can heal even large cartilage defects and an injectable fluid that repairs early signs of cartilage injury. While the FDA has not yet approved these treatments, the company has used them to treat large and small defects in large animal models.

Rethinking Success

After reviewing his work, Athanasiou shifted gears and talked about his own pathway through life. Along the way, he took an axe to many of the preconceptions that people have about success.

After reviewing his work, Athanasiou shifted gears and talked about his own pathway through life. Along the way, he took an axe to many of the preconceptions that people have about success.

He started with the belief that it takes educated and wealthy parents who show children how to succeed. He showed a picture of his mother, who left school after the fifth grade, and his father, a painter who never went to school, but taught himself to read, write, and do math. Athanasiou himself is the product of expensive U.S. universities that his parents could never afford. “What I’m trying to say is it is difficult, but it is doable,” he said.

He challenged the notion that children need to focus early to achieve success. He pointed to expecting parents who play Mozart for a fetus, and to moms and dads who whisper to their children, “Let me show you how we solve equations using the Laplace transform.” Athanasiou said he had no idea what he wanted to do when he was young, though at one time he was fixed on becoming a bank teller. As he grew older, his interests and education led him to biomechanical engineering.

Then there is the matter of intelligence. “Yes, you have to be intelligent,” he said. “You know what? Everybody here in this room, we are all sufficiently intelligent to achieve whatever we want. If you’re here, you’ve already passed that test.”

He argued that what really counts in life is a well-developed sense of principles and values. In his case, this involved pursuing excellence with passion in whatever he does. “My father was a house painter, and he always pursued excellence in his job, and I try to do the same thing,” he said.

Everyone must enjoy what they do, or life will be miserable, he noted.

Researchers, in particular, need to develop a thick skin. “Most grants are rejected,” he said. “We’re in the business of rejection. When you get a rejection, go home and cry, but get out the next morning and keep at it. That’s the business we’re in.”

Since we are all going to die, we have to ask what we want out of this life. What should our legacy be? For Athanasiou, his goal is the full use of his talents and excellence to pursue eudaimonia, the Aristotelian concept of human well-being. “On your deathbed, you should be able to look at your family, your students, and whomever you influenced and say, ‘I’ve done well, and I have helped society at large.’”

He believes in taking breaks. “I’ve done some of my best work on sabbaticals,” he said. He also encouraged researchers, some who struggle just to stay current in their own fields, to become polymaths and explore the arts and humanities to broaden their thinking.

Toward the end of his talk, Athanasiou showed a complex Medieval-looking painting. Some of his former students in the audience, now professors themselves, began to laugh. He has shown this picture to graduate students for years, asking them to describe it in a few sentences.

Many enumerated what they saw, the animals, cups, and tree branches. One student, however, said the image epitomized the system that disadvantages working people.

“I was shocked, but then I thought about it and said, ‘What a great answer,’” he said. “You know why it’s a great answer? Because to get the most comprehensive understanding -- to think outside the proverbial box -- your team needs as much diversity as possible -- ethnic, racial, gender, opinion, educational background, and thought process. I believe that diversity is the cornerstone of excellence.”

He concluded by reaffirming how a passionate commitment to excellence can change lives. “There are no boundaries or artificial walls,” Athanasiou said. “If a house painter’s son can find his way in a foreign country and stand on this podium, everybody can do it. Really. So, don’t let anybody create those artificial walls around

Check out the condensed program and schedule at-a-glance for the fall’s BMES Annual Meeting in San Diego, Calif., now posted here: ...

BMES was proud to be represented at the recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) workshop last week, Cancer &...

Because we understand the complexity of this year’s funding and travel uncertainty, we are extending the abstract submissions deadline for this...

Want to make an impact? As a CDR reviewer, you’ll evaluate submissions from student chapters and help determine which ones deserve top recognition....

We are seeking passionate members to join the prestigious BMES Awards and Fellows committees and play a key role in helping us recognize excellence...

Innovator, BMES Fellow, and University of California, Irvine Distinguished Professor, Kyriacos A. Athanasiou, has centered his approach to...